The EU’s Energy Union – An Opportunity for the Western Balkans

By Dimitar Bechev*, 11 mars 2015

Policymakers and pundits in the Western Balkans should take note as energy has once more come into the spotlight in Brussels. On February 25th the European Commission unveiled its blueprint for an Energy Union, an instrument intended to both deepen integration and bolster EU’s bargaining power vis-à-vis external suppliers such as Russia’s Gazprom. While the final version falls short of the ambitious proposals tabled back in spring 2014, by the then Prime Minister Donald Tusk and his first diplomat Radek Sikorski, it hopes to advance interconnectivity of gas and electricity grids across national borders, roll back vested interests, bring down prices and improve security of supply.

Policymakers and pundits in the Western Balkans should take note as energy has once more come into the spotlight in Brussels. On February 25th the European Commission unveiled its blueprint for an Energy Union, an instrument intended to both deepen integration and bolster EU’s bargaining power vis-à-vis external suppliers such as Russia’s Gazprom. While the final version falls short of the ambitious proposals tabled back in spring 2014, by the then Prime Minister Donald Tusk and his first diplomat Radek Sikorski, it hopes to advance interconnectivity of gas and electricity grids across national borders, roll back vested interests, bring down prices and improve security of supply.

Why should the non-members in the Western Balkans care? The non-member states should care because their geographical location is of particular importance. Any meaningful effort to complete the single market in energy cannot bypass the enclave of ex-Yugoslav countries and Albania tucked inside the EU. Secondly, the Western Balkans are an integral part of the EU-sponsored Energy Community; a regional institution headquartered in Vienna which also involves Moldova and Ukraine. Its core purpose is to speed up the harmonisation with the EU rules in the area of energy, even in advance of formal membership talks. In other words, whatever new legislation comes through in response to the Commission’s proposals it will, sooner or later, reach Belgrade, Podgorica and Tirana.

Yet the most serious reason to pay attention to the Energy Union is that it highlights cooperation at the regional level. If implemented it will bind the area closer together, help modernise its energy sector and contribute to economic development. The Commission takes an inclusive approach as to what is meant by the term “region” – the Western Balkans are flanked by neighbours already inside the EU, e.g. Greece, Croatia, Hungary, Bulgaria, Romania etc.

“Given its particular vulnerability, there is a need to improve cooperation, solidarity and trust in the Central and South-Eastern part of Europe. Dedicated cooperation arrangements would help to accelerate the better integration of these markets into the wider European energy market which would improve the liquidity and resilience of the energy system and would allow full use of the region’s energy efficiency and renewable energy potential. The Commission will take concrete initiatives in this regard as an urgent priority.” (p. 11)

As such, there are several points worth noting.

The Western Balkans, as well as the wider South East Europe, have considerable potential in areas such as renewable energy. In Albania hydropower alone accounts for 20% of gross domestic consumption and close to 100% of electricity production. Montenegro, which is also expanding biofuels, comes second with 17%. But to tap the full potential in renewables, including geothermal, solar and wind energy, it is essential to establish better cross-border infrastructure through investing in high-tech grids and developing storage capacity. As underscored by my friend and colleague Julian Popov, the former environment minister of Bulgaria who is now based at the European Climate Foundation, “The daily and seasonal variability of renewable electricity generation is best balanced within a power grid spread over larger territory, linking a wider variety of power generation and storage facilities.” If energy efficiency measures are adopted, the Western Balkans can make huge strides towards becoming self-sufficient – and gradually decrease their dependence on hard fuels such as lignite.

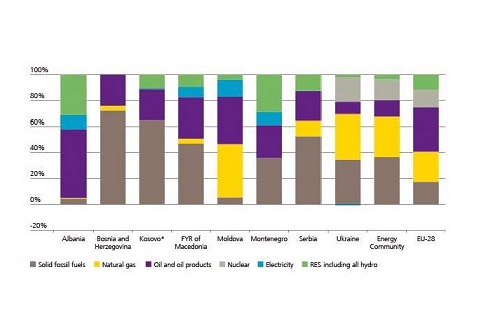

Furthermore, there has been much hype in the region with regards to gas. Coupled with disappointment over Vladimir Putin’s announcement last December that the South Stream pipeline was off the table and was to be replaced by the “Turkish Stream”. In Serbia and even Macedonia, which was hoping for an offshoot to its territory, the pipeline was seen as an excellent business proposition. Moreover, international media are full of stories about the Balkans’ almost complete dependence on Russian gas supplies and the freeze during the 2009 standoff between Moscow and Kyiv is well remembered. While Macedonia and Bosnia and Herzegovina are reportedly paying Gazprom the highest prices in Europe. However, in reality the picture is more nuanced. The relative share of gas in the overall consumption is low. In the Western Balkans, Serbia comes on top No 1 with 11% or 2.5 bn cubic meters (bcm) a yearwhileby comparison Croatia consumes 3 bcm of which two-thirds is extracted from its own deposits in the Adriatic. Put differently, the dependence on Russia is not as overwhelming as it looks at first glance (see Figure 1).

The Energy Union offers the region an opportunity to obtain access to alternative suppliers – and therefore bring prices down while gradually expanding the share of gas in electricity production, heating and, hopefully, industry. One of the priorities of the Energy Union is to advance the so-called Southern Gas Corridor. This Corridor will kick off towards the end of this decade once 10 bcm of gas from Azerbaijan starts flowing via Greece and Albania through the Transadriatic Pipeline (TAP). The projected Liquefied Natural Gas (LNG) terminal on Croatia’s island of Krk will bring new volumes to consumers across South East Europe as well. This will result in increased competition – especially in light of the expectation that LNG prices on are to go down on the world market. The high interest by business in the recent tenders for offshore oil and gas exploration in Croatia is an encouraging sign while Petromanas Energy and Royal Dutch Shell are also drilling in Albanian waters.

As always, there are a host of caveats. Firstly, the countries of the region will need to mobilise both private investment and EU funds into developing badly needed infrastructure. Secondly, comprehensive reform in the sector is needed to ensure greater efficiency as well as transparency. Due to the fact that liberalisation measures, e.g. phasing out subsidies, might hit vulnerable social groups across the region it will be essential to come up with compensatory policies to cushion the negative effects.

In summary, the EU’s focus on energy policy offers opportunities for the Western Balkan to reap economic benefits as well as contribute to the Union’s energy security. It is imperative for decision-makers in Brussels, EU capitals and the region to seize those opportunities and ensure the proposed Energy Union works also for countries that are still on the accession track.

* Dimitar Bechev is a Senior Visiting Fellow at the European Institute, London School of Economics (LSE). Until 2014 he was a Senior Policy Fellow and Head of the Sofia Office at the European Council on Foreign Relations. He is also affiliated with South East European Studies at Oxford (SEESOX), a research programme based in St Antony’s College, Oxford. He received his D.Phil. in International Relations from the University of Oxford where he taught in 2006-10. He was a visiting professor at Hitotsubashi University in Tokyo and currently lectures at Sofia University, Bulgaria.

Libraria Shteti Web

Libraria Shteti Web